The 5 Changes Every Operator Must Know About the New Ministerial Order TDF/149/2025

If you are an operator or work in communications, you are likely aware that on Saturday, February 15, the Ministerial Order TDF/149/2025 was issued—somewhat unexpectedly, it must be noted—“establishing measures to combat identity theft scams via fraudulent telephone calls and text messages.” You have probably read dozens of articles outlining the significant change, specifically that “commercial calls from mobile lines will no longer be permitted, and only toll-free numbers (800/900) will be authorized to contact you.” However, the new Ministerial Order TDF/149/2025 includes several minor modifications for operators that affect communications across all types of companies.

The primary objective of this Ministerial Order is to address telephone operators (not data operators) and is primarily aimed at preventing fraud and identity theft scams. In other words, it is designed to prevent scenarios where a scammer calls using your bank’s number or sends an SMS displaying the bank’s name when the sender is not the bank.

Nonetheless, many people consider it a “scam” or “attempted scam” when they receive calls from an unknown number “masquerading” as their telecommunications or energy provider, even though these are commercial calls made by companies contracted by these providers to acquire new customers.

Furthermore, the new Ministerial Order seeks to eliminate this method of customer acquisition. To begin with, it establishes substantial fines for non-compliance, indicating that enforcement will be taken seriously. In addition, the Ministerial Order TDF/149/2025 entails many other important changes in the telephone network, operators, and companies that have been overlooked by clickbait websites. We will now discuss these changes, which are set to significantly alter the industry landscape.

Prohibition on making commercial calls from mobile number ranges.

Let’s first discuss the most striking aspect, which has sparked comments nationwide: starting on June 7 (20 days plus 3 months from the BOE publication), no call center—and, as noted in the BOE, no sales representative from any company (does this mean goodbye to mobile phones for sales reps?)—will be allowed to call you to sell something using a mobile number as they have done until now. As stated in Article 10.1: “The segments N=8 and 9, for the zero value of digits X and Y, of the national telephone numbering plan, in addition to automatic reverse charge services, customer service, and the making of unsolicited commercial calls, are allocated.”

In other words, for customer service numbers as well as for commercial calls, only 800 or 900 reverse charge numbers (with the call cost borne by the recipient company) should be used.

Will commercial calls be allowed from fixed-line numbers?

Although all media outlets have reported that commercial calls may only be made from 900 numbers, it is interesting that the BOE itself does not expressly prohibit fixed-line numbers (it would have been straightforward to clarify and ban both mobile and fixed-line numbers for commercial calls). Only mobile numbering has been explicitly prohibited. However, since this issue was not clearly addressed in the BOE, an update from the Ministry on February 24 also includes fixed-line numbers for commercial calls: “Companies shall not use mobile numbers for telemarketing. They must use geographic numbers or 800/900 numbers, now authorized to make calls.”

To clarify: commercial calls from mobile numbers are prohibited starting May 15 (an updated date also mentioned in the Ministry’s press release), which is slightly earlier than the originally indicated June 7.

It should be noted that 900 numbers are also used for customer service, so if we want to receive calls regarding changes, incidents, or other matters, we need to ensure these numbers are not blocked, otherwise we will not receive any calls.

Let’s clarify an important point: what constitutes an unsolicited commercial call?

Firstly, the BOE refers to “unsolicited commercial calls.” This means that a call center may have your prior consent to call you, but you did not request the call at that moment. Remember that for a call center to contact you, they must have obtained your explicit consent. You likely provided such consent when filling out a form—whether when signing the contract for your bank’s new credit card update, accepting any agreement, creating an account on a website, or making your most recent online purchase.

A commercial call is defined as a call in which someone contacts you exclusively to offer a product or service.

- Is a survey a commercial call? No.

- Is a call from a political party a commercial call? No.

- Is a call from an electricity company informing you of a billing error a commercial call? No.

- Is a call from a telecommunications company inquiring about an individual named Jose Emilio who was interested in a service a commercial call? Yes, but if you are not Jose Emilio, it is a misdirected call—a data error rather than a properly targeted commercial call. You may report it; however, since it was caused by erroneous data, it could be considered an “administrative error” (as if I had given consent to be called but provided your phone number instead).

If you registered via a website form and then received a call, this is considered a commercial call. However, since you signed up and provided your consent, the call is permissible—unless you are on the Robinson List, in which case calls are not allowed.

Strict Use of Numbering for Outgoing Calls

Currently, Spanish law prohibits caller ID spoofing. Although some telecommunications experts writing on network forums may disagree, no one is allowed to arbitrarily select any number—even if they have an Asterisk system and wish to identify with someone else’s number. The operator will block such calls and prevent the use of a number that does not belong to the caller. This level of control over numbering is not common in some non-European countries, but in Spain, it is tightly regulated.

Until now, if you have been assigned a telephone number by an operator (for example, your mobile), you could request another operator to allow you to make calls using “your number.” After all, it is your number and you have given authorization for it to be used on your PBX for outbound calls. However, it appears that this practice is coming to an end, or at least it will become much more complex. It will require guarantees that the number in question truly belongs to you, and even then, new legislation will mandate number porting if you wish to place calls through a different operator.

It is also officially prohibited to make calls using numbering that is neither assigned nor sub-assigned to any operator, or that does not belong to any end user. While an operator may prevent one of its subscribers from using numbering that is not allocated within its network, the challenge lies in determining whether an incoming call uses a number that has not been assigned to any user. The BOE does not explain this, yet it mandates that incoming calls using unassigned numbering be blocked. How will it be determined if the incoming number (from another operator) belongs to a subscriber or is an unallocated number? The CNMC will require all operators to provide a list of their subscribers and the numbering they use, and it will develop an API that operators must query each time they receive a call to verify whether that number belongs to someone.

The Ministry has given the CNMC until May 15, 2026, to develop this tool and for operators to begin using it.

This opens up another interesting issue…

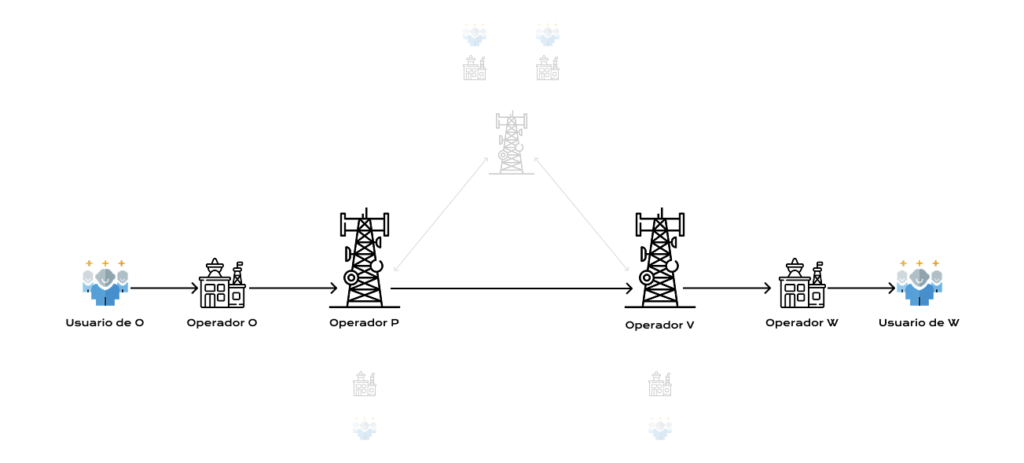

As explained in the article on assignment and sub-assignment of numbering, telephone numbers are allocated by the CNMC to network operators, who in turn sub-assign them to other operators for use with their clients and users. Can the sub-assigned numbering from one network operator then be used on another? In principle, yes—it is possible, as network operators could verify that the number belongs to the operator initiating the call. However, how will they determine whether that number actually belongs to a valid user or is unassigned? The CNMC will need to clarify these uncertainties.

Only numbering that has been previously assigned or sub-assigned will be used.

As explained in the article on “what assignment and sub-assignment mean,” there are many operators (let’s call them P) (transit operators) who, instead of sub-assigning numbering, allocate numbers as if they were for their end users. This practice has always been overlooked; however, now transit operators (both Operator P and Operator V) must block such numbering, since it does not belong to Operator O.

Forbidden Use of One Operator’s Numbering on a Different Operator

The new Ministerial Order mandates that operators block incoming calls if the numbering belongs to the operator that is the intended recipient of the call.

For example, consider the case of Jaime, who uses an IP operator for his company’s calls. He wishes to make calls using the number associated with his Movistar fiber connection, so he contacts his IP operator, TuOperadorIP, to enable the use of his Movistar number in addition to the operator’s own numbering. After sending his invoices and signing two contracts, TuOperadorIP grants him the ability to place calls using the Movistar fiber number.

Up to this point, everything proceeds normally. Jaime utilizes TuOperadorIP for outbound calls, as his PBX is configured accordingly, allowing him to use his fiber number. Incoming calls are directed to the office landline, and all functions smoothly.

However, when Jaime calls his wife’s mobile phone—which is also with Movistar—Movistar suddenly blocks the call. Why? Because Movistar is invoking the new law that permits them to block calls if the call originates from an external provider and the number is registered to Movistar.

Therefore, it is prohibited to call a Movistar user using a provider other than Movistar if the Movistar numbering is used.

How is this issue resolved? The solution is to “port the number” to the operator with which you wish to make calls. This matter could spark an interesting debate, as many users are unable to port their number because their primary number is tied to their fiber line. In short, this is yet another reason to decouple the number we favor from the fiber connection.

Forbidden Use of National Fixed-Line Numbering for International Calls and Companies

According to the interpretation of the BOE, the use of national numbering for international calls is also prohibited.

In a VoIP environment, where all calls are made over an IP network, “international calls” are defined as those originating from non-national companies.

While a mobile number can belong to a foreign individual, a fixed-line contract requires the physical presence of a national address. Therefore, it is not permitted for foreign companies to present international calls using national fixed-line numbering. This effectively prohibits the assignment of fixed/geographic numbering to companies that are not physically located in Spain or that do not have a headquarters or representative office in the country. Although this was already the case, enforcement will now be much stricter. If a foreign company wishes to obtain national fixed-line numbering in a specific province, it must have a branch in that province, necessitating some form of corporate documentation (e.g., an invoice) with an address in that province.

This measure aligns with practices already in place in several European countries (such as Portugal, France, and Germany), whereas in Spain, until now, companies could obtain Spanish numbering without having a physical domicile in the country.

Strict Limitation and Strict Control of SMS Origin

Although it may seem odd (I’ve always found it curious), SMS messages have traditionally enjoyed a certain degree of freedom. SMS has essentially been “a message sent to a mobile phone,” where the originating field (the “from” field) served merely as an identifier and never as a means of authorization. This means that it has been possible to send SMS messages with any origin, including names (aliases) to help the recipient identify who is sending the message.

However, as is often the case, freedom is highly valued—but great power comes with great responsibility. When that power is misused to cause harm, it becomes necessary to impose limits on such “freedom” and exercise tighter control over who is permitted to do what.

For this reason, SMS messages have increasingly been used as a vector for scams, tricking individuals into visiting fraudulent websites, submitting personal data, or even initiating bank transfers. Consequently, the Ministerial Order includes a specific section on the proper use of SMS to help prevent scams and fraud.

Mandatory Use of a Public Registry for ‘Alias’ Usage in Caller Identification

In light of the fact that this functionality has been exploited to commit numerous crimes and frauds, the origin of the SMS will be restricted to the telephone number of the user or company sending the message. If an alias is to be used, that name must be registered in an official registry associated with the sending company. Essentially, this measure is designed to prevent third parties from sending messages under aliases such as “BANK XXXXXXX” to defraud users.

What About RCS Messages?

There was an expectation that RCS messages would help address this issue. According to some reports, it was believed that RCS would eventually replace SMS. RCS messages require a bureaucracy (verifiers, documentation, contracts, etc.) to ensure that the sender can be correctly identified and that the message is authorized and verified by a controlling entity. One problem, however, is that RCS is largely managed by external companies like Google (or Huawei), meaning that the identification, verification, and certification policies are based on these external entities. With this change, SMS will be granted much greater control and security, with operators and the CNMC overseeing that companies send SMS with their official identification.

The Ministry has given the CNMC just over a year—until May 15, 2026—to develop the tool for registering alphanumeric codes in SMS.

A Brief Opinion…

I cannot deny that if these measures help reduce spam—especially for those enrolled in the Robinson List—it will be a positive outcome. However, my primary hope is that these measures will help prevent fraud and deception.

Unfortunately, not all laws in this country have managed to stop us from receiving automated calls with job offers, even though it would be quite easy to identify who is behind those calls. Thus, if the prosecutor’s office, the police, the CNMC, the AEPD, and the Ministry of Digital Transformation cannot prevent these calls, the only recourse may be to enact laws that force operators to cease these activities under the threat of hefty fines.

Requiring operators to generate semi-annual blocking reports, to consult databases for every received call, and to implement so many changes in their infrastructure that it becomes an odyssey… this is what awaits us from now on. Only those operators with an engineering department capable of carrying out the necessary infrastructure modifications will be able to comply with the BOE’s requirements. Otherwise, they will have to rely on larger network operators to support and assist them with the extensive list of changes that must be implemented within months.

Out of the nearly 1,000 telephone operators registered with the CNMC, how many do you think control their infrastructure well enough to modify their systems to adapt to these changes? The majority will likely reuse services from larger operators to avoid legal issues.

I foresee very intense and interesting changes and movements among the country’s telephone operators this year.